Both Ma and the school are a snapshot of education in Dongxiang. The county, with 284,000 residents - mostly Muslims - in Gansu province, is grappling to earn a passport to progress by prioritizing education.

.jpg)

Fourth-grader Ma Lianghai (left) and third-grader Ma Linxiang are engrossed in their work during art class at Zhaojia Elementary School in Dongxiang, Gansu province, on Sept 18. [Photo by Xu Jingxing/China Daily]

Poverty-stricken county works to ensure every school-aged child has access to education, Zhu Zhaoxu reports from Dongxiang, Gansu.

Thirteen-year-old Ma Qidong looks smaller than his urban counterpart, but listens as attentively to the teacher as any diligent student.

The sixth-grader at the sprawling Gudu Elementary School uses a flour sack as his schoolbag to carry two dog-eared exercise books and an English textbook that has not been used since the school year started nearly a month ago.

Both Ma and the school are a snapshot of education in Dongxiang. The county, with 284,000 residents - mostly Muslims - in Gansu province, is grappling to earn a "passport to progress" by prioritizing education.

The ethnic minority autonomous county is as large as London in area, but comparisons end there - its residents mostly inhabit a bleak terrain of 1,750 ridges and 3,083 valleys, envying the prosperity lifting other parts of China.

"Dongxiang admittedly lags behind most parts of China in terms of its economy and in many other fields as well," Gao Shitai, Party secretary of Dongxiang, said. "But the most glaring disparity lies in education."

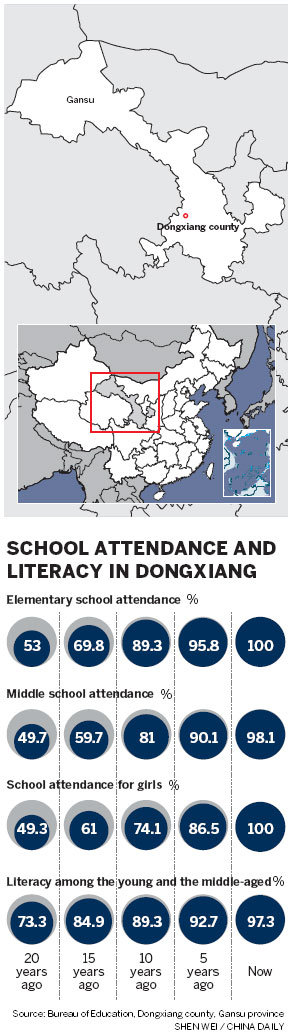

The average Dongxiang resident has only 3.7 years of education, according to Gao; the national average is 8 years.

"For this ethnic minority to survive and thrive we have to vigorously develop education. Without education there is no solid foundation," Gao said.

The Gudu school on a mountainside in Dashu, one of 24 townships in Dongxiang, is about a 40-minute drive from Suonan town, the county seat of government.

Most of the road is a rough dirt path, hewed by leveling hill slopes. On fair days, passengers are shaken and stirred; in the rains, driving is well nigh impossible.

"When the weather is fine, we have 24 students attending school, but two or three are allowed to be absent whenever it snows or rains, because it is perilous for the youngsters to trudge through ranges and ravines," said Ma Tenghui, headmaster of the Gudu school.

The campus, whose number of students has hovered around 30 since it was founded in 2001, was one of 56 basic schools Dongxiang authorities set up over the past decade to make attending schools more convenient.

Children used to walk up to 10 kilometers to reach the nearest school, and nearly 11 percent of school-agers failed to attend elementary schools 10 years ago, indicate figures from the Dongxiang Bureau of Education.

The county now has 190 elementary schools for boys and girls aged between 7 and 12, boasting a nearly 100 percent school attendance rate, according to bureau chief Zhang Xuelong.

English teachers wanted

For a county where 96 percent of the population are farmers with annual per-capita income below 2,000 yuan ($317) in 2010, every cent counts when it comes to running schools.

In the case of Gudu school, a community school better known as Gudu "teaching spot" locally, educational authorities have arranged for Ma and his wife to work at the same facility to cut costs.

The couple and another teacher teach five classes in the only two classrooms available, meaning teaching is done by rotation.

Though English textbooks are given free to the pupils as with other books and tuition the subject is not taught at Gudu school due to a lack of teachers.

Besides Gudu, five other elementary schools in Dashu township do not have an English class. Only four schools in the township of 8,000 folks manage English lessons, usually taught by math or Chinese teachers for two hours a week, according to Ma Jinlong, headmaster of Dashu Central Elementary School.

Education bureau chief Zhang said Dongxiang is apparently not attractive to graduates of English-language institutes.

"We welcome volunteers from English-speaking countries to help us," he said. "Preferably, I hope they stay here for a year or longer, not just for one- or two-month sessions."

English-speaking volunteers stoke great interest of the pupils in the language; but as soon as they leave, the students' interest flags drastically, he said.

They then have to face the stark fact of either having no such lessons or being taught by teachers without adequate skills, Zhang said.

"But if the native speakers stay longer, they could help train our teachers in addition to improving the children's linguistic skills," he said.

.jpg)

Ma Xuemei (third right), a Chinese language teacher for second-graders, poses with her colleagues at Zhaojia Elementary School in Dongxiang. [Photo by Xu Jingxing/China Daily]

Boarding schools

While Ma Qidong and his peers at Gudu and other elementary schools can dispense with English as a luxury, they cannot avoid the risk of dropping out of school some day.

Gudu is among the few "teaching spots" that have six grades, as most have classes for first three grades only.

This means nearly 4,000 students at the "teaching spots" have to trudge longer distances to attend other schools after finishing their third grade, according to Zhang.

The "teaching spots" are designed to offer the nearest places for younger children to study for three years, after which they are supposed to be able to walk farther to attend "conventional schools", said Zhang.

"That's why building boarding schools is such a priority for us," he said.

Only 17 of 211 elementary and high schools provide lodging, with subsidies going to 9,066 boarders, half of them elementary school pupils, according to bureau figures.

At present there are nearly 60,000 elementary and high school students in Dongxiang.

"Boarding schools are a magnet for children plagued by the daily trouble of walking long distances," Zhang said, adding Dongxiang plans to build 29 such schools by 2015, at least one for each township. But even though a boarding school is available, poverty can be a severe impediment for many families.

Ma Qiyuan, elder brother of Ma Qidong of the Gudu school, stays at home as he suffers from epilepsy that the family cannot afford to treat.

The family lives a five-minute walk from the Gudu school. The mother, Ayingshe, 50, said her 15-year-old son had enrolled in Dongxiang Minzu High School, a boarding school, but 70 yuan a week for transport and food was quite a burden for the family of five.

The Mas' earthen house was knocked down last year because it leaked water when it rained. The township government helped build a brick house for the Mas, in addition to providing 500 yuan a year for each family member.

The Dashu township chief, surnamed Ma (the family name is quite common here), promised the township government would try to help get Ma Qiyuan back to school.

About 108,000 residents, or nearly two in five of Dongxiang's population, claimed government subsistence allowance last year, according to local government sources.

Unlike Ma Qiyuan, who fell ill, Ma Shiming was forced by his mother to quit school two years ago to herd sheep and look after his two sisters aged below 5.

"I begged my mother to let me return to school, but she said she needed help, as father was a migrant worker far away from home," the 14-year-old at Machang Elementary School in Wujia township said.

His teacher, Ma Jinming, called the father several times, imploring him: "You can't write your name and have difficulty even in finding the right bus; do you want your son to end up like you?"

The son promised his mother, if permitted back to school, he would study harder to win as many prizes as possible.

Back at school, he is one of the happiest students; and has won five certificates of honor by grade five.

Gao Shitai, the Dongxiang top official, said the county has left no stone unturned to ensure every school-aged child receives education.

Even with skimpy annual revenue of 45.9 million yuan in 2010, Dongxiang funneled 15 million yuan, or a third of the total, to reward schools, schoolmasters, teachers and students with top performance, he said.

Wings' for migrants

As export of labor is a major source of income for residents, Gao said education makes sense to migrant workers as well.

Most of Dongxiang's 65,000 migrant workers perform tough, manual or tedious jobs, such as washing dishes in restaurants or building and maintaining roads on the Tibetan plateau.

They would have a much better life if they are better educated, Gao said.

Migrant work contributed 29 percent to local farmers' income last year.

"The Dongxiang ethnic group is very intelligent and diligent," Gao said. "They should be endowed with wings of knowledge to fly higher."

Staying in school

To curb the school dropout rate, the government has launched an extensive campaign to publicize the Compulsory Education Law, with banners and slogans exhorting the value of education posted in virtually every village in Dongxiang.

Government employees at various levels have also signed "agreements" with local schools to help dropouts get back to school, Gao said.

Zhou Wenhua, an imam at Qiangtou Mosque, one of the 38 mosques in Zhaojia township, said: "Islam stresses the importance of education, so at each religious gathering, I preach the teachings, encouraging parents to ensure their children have decent schooling."

Over the past three years, 2,100 junior high students and 680 elementary students have returned to school after initially dropping out, according to education bureau statistics.

Back at Gudu Elementary School, its headmaster Ma is experiencing another rub in Dongxiang's education.

"We may have to bid adieu to Gudu and go where there is a kindergarten for my child, now 3 years old," he said.

There are only three kindergartens in Dong-xiang catering to 386 kids, while the number of children aged 4 to 6 is 15,094, according to the latest statistics of the education bureau.

As the language of the Dongxiang ethnic group is only oral, it is imperative for more children to attend kindergartens, since bilingual education at an earlier age will make them linguistically prepared to receive schooling and interact with people outside Dongxiang, said bureau chief Zhang.

The county has decided to set up 26 kindergartens in five years to solve the problem facing people like headmaster Ma, he said.

As with other projects in the education sector, building kindergartens and boarding schools needs financial support from agencies at both provincial and national levels, he said.